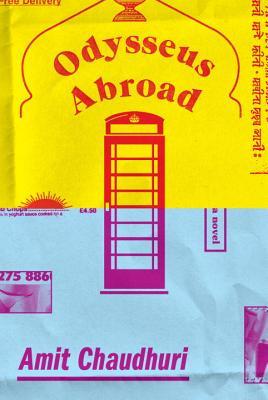

East meets West in Amit Chaudhuri’s latest, set in ‘80s London. Ananda Sen is a young graduate student of poetry hoping for small measures of success, depending on his much older uncle Ranagamama, who has parked himself in a rent-stabilized bedsit for years, for companionship. Unfolding over the course of one Sunday afternoon, the story, in typical Chaudhuri style, is not packed with external events, focusing instead on the trials of displacement and non-conformity in a strange land. Uncle and nephew’s endless reflections occasionally feel too self-absorbed; nevertheless Chaudhuri’s gorgeous writing and insightful observations ultimately deliver a soulful novel.

Showing posts with label Immigrant Experience. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Immigrant Experience. Show all posts

Wednesday, March 18, 2015

Friday, February 14, 2014

Family Life by Akhil Sharma

Growing up is hard enough. Imagine doing so as a new immigrant where your family is still navigating the parameters of the adopted country. That’s harder. Now top this all off with the crushing weight of immutable circumstances brought about by unspeakable tragedy. This, shows Akhil Sharma in his bleak moving novel, is no ordinary “family life.” While Ajay’s parents lean on different crutches to live with extreme pain, he must carve a path through the haze to some kind of redemption. Crafted with elements from his own life, Sharma delivers an entirely brilliant take on the popular coming-of-age story.

Tuesday, January 14, 2014

Little Failure by Gary Shteyngart

The only child of Russian Jews, Gary Shteyngart travels from a shaky asthmatic beginning in St. Petersburg as Soplyak or Snotty to middle-class comfort in New York. While tales of immigrant angst abound, Shteyngart is especially skilled at exposing the layers of heartbreak under his polished veneer of humor. As he desperately tries to shake what he terms his “beet salad heritage” and make peace with his parents’ questionable parenting skills, Shteyngart’s affecting memoir shows just how insidiously our past shapes us -- in both good ways and bad. That kid on the cover has sure ended up going places!

A longer review of this book will be published in the February 5 issue of The BookBrowse Review. Thank you to the publishers for an ARC.

A longer review of this book will be published in the February 5 issue of The BookBrowse Review. Thank you to the publishers for an ARC.

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Review: Pigeon English by Stephen Kelman

Who’d chook a boy just to get his Chicken Joe’s?

Pigeon English by Stephen Kelman

Around ten years ago, a young Nigerian immigrant, 10-year-old Damilola Taylor, was beaten by boys barely older than him in Peckham, a district in South London. Damilola later bled to death. The incident sparked outrage in the United Kingdom and was subsequently pointed to as proof that the country’s youth had gone terribly astray.

The same incident seems to have also inspired a debut novel, Pigeon English, with 11-year-old Harri Opoku filling in for the voice of Damilola Taylor. As the book opens, Harri has recently emigrated from Ghana to London with his older sister and his mother. Dad and younger sister and the rest of the family are still in the native country and Harri is often brought back to his home country through extended phone calls exchanged between the two sides.

Like most children, Harri is not privy to the intricate goings-on in the lives around him. It’s a fact made worse by the displacement brought about by immigration. Harri must not just figure out the ways of the world, he must do so in a new place where the rules of the game are entirely unfamiliar. Even if life in the ghetto is painful and lived in extreme poverty, Harri finds plenty to keep him in good spirits. For one thing, he wants to try every kind of Haribo (candy) in the store close to him.

Even better he has struck a tentative friendship with a local boy, Dean. With Dean’s help, Harri is determined to solve a recent crime—one where a kid like himself is found brutally murdered in a struggle over a fast food meal. The devastating tragedy affects Harri deeply and he is determined (in a typical naïve and childish way) to find the killers. Unfortunately he gets too close to the real killers—people who might not appreciate interference from a bright-eyed curious kid.

Pigeon English is narrated through Harri’s voice so the English is broken and mixed in with special words whose meanings become apparent only after a few readings. “Bo-styles” for example, means very good while “Asweh” is the more readily understandable, “I swear.”

Harri’s musings and experiences can be funny at one moment and heartbreaking the next. Author Stephen Kelman has done a terrific job in capturing the boy’s voice. The problem with Pigeon English is that the same voice eventually becomes a distraction. It never becomes seamless enough so the reader can concentrate on what the boy is saying—you’re forever hung up on how he’s saying it. And of course there are times when he says too much: “I can make a fart like a woodpecker. Asweh, it’s true. The first time it happened was an accident. I was just walking along and I did one fart, but then it turned into lots of little farts all chasing it.” Did we really need to know that?

It was entirely a coincidence that I read this novel right around the time that the London riots made headline news around the world. As was reported by the New York Times and other news outlets, it was the youth who were the primary looters and criminals in these riots—an effect brought about by a “combination of economic despair, racial tension and thuggery.” The riots, the paper reported, “reflect the alienation and resentment of many young people in Britain.” Read at this particular moment in history, Pigeon English then seems much more than a fairly good read—it also comes across as an important one. One can’t help but wonder how much the timely relevance of its subject matter lead Pigeon English to be shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize this year.

“I made the choice, nobody forced me,” says Harri’s mother about the decision to move her kids to London from Ghana. “I did it for me, for these children. As long as I pay my debt they’re safe and sound. They grow up to reach further than I could ever carry them.” Pigeon English is a moving novel not just because it is a stark story about London’s ghettos, but because it reminds us that for many in the developing world, a move to this kind of a hell is actually a move up.

This review was originally published in mostlyfiction.com.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)