Friday, July 31, 2020

The Glass Kingdom by Lawrence Osborne

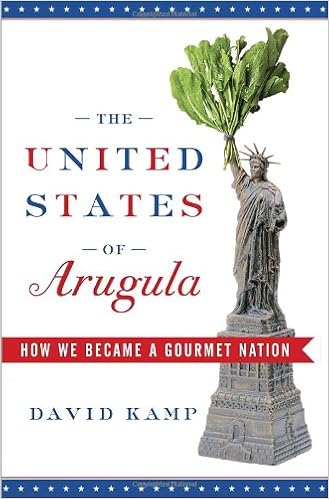

The United States of Arugula: How We Became a Gourmet Nation

It might make sense today that Lady Liberty is holding aloft a bunch of arugula but remember when President Obama got flak for complaining about the rising cost of the greens? This rollicking book, published in 2006, chronicles how U.S. French dining made way for California and New American haute cuisine. It profiles a series of chefs along the way; Julia Child, Wolfgang Puck, Alice Waters all get prime time. The book misses connecting the dots between these chefs and everyday people though: what changed in society that made people embrace microgreens and kombucha? An entertaining if incomplete history.

Saturday, July 25, 2020

Street Without a Name: Childhood and Other Misadventures in Bulgaria by Kapka Kassabova

The Tummy Trilogy by Calvin Trillin

Get your silverware ready and tuck into these wry tales with one of America’s favorite food writers. I love Calvin Trillin’s work in the New Yorker and admire his passion for chasing after good eats. These volumes are peppered with an empathetic look at food and the people who love it, like Fats Goldberg, the pizza baron.After digging into this trilogy I realize though that his food commentary is best eaten like an amuse bouche, a little at a time to whet the appetite. Too much gluttony makes even the best food too rich and you tire of it.

Saturday, July 18, 2020

The Devil's Cup: A History of the World According to Coffee by Stewart Lee Allen

Friday, July 17, 2020

Villa Pacifica by Kapka Kassabova

Sunday, July 12, 2020

Migrations by Chalotte McConaghy

Friday, July 10, 2020

Chasing the Monsoon by Alexander Frater

A native of Mumbai, known for its biting wind-driven monsoons, I was excited by the premise of this book: chasing the first monsoon rains all across India. Frater, an Englishman, starts from the very southern state of Kerala and moves north on to Goa, Mumbai, a huge jump to Delhi, Kolkata and on to Cherrapunji, the wettest place on earth.

The travelogue that emerges is witty and engaging told with generous doses of empathy. I especially loved the sections on Trivandrum and Cherra. Because the author has to chase after the breaking of the monsoon across the subcontinent, he doesn’t linger. Which is a pity because after the initial joy comes the weary dampness that seeps into your very bones, which too would have made for great reading and a more measured view of the live-giving rains.

It’s hard to ignore the white colonial gaze here. Yes, it takes an agonizing two weeks and a painful walk through the notorious Indian bureaucracy for Frater to receive permission to visit Cherrapunji but only a native will recognize how easy it is otherwise for the author to lean on his whiteness to get access. At one point, Frater describes how Herman Kisch, a British Civilian officer, staved off devastating famine in India. While indeed commendable, I couldn’t help but roll my eyes at Frater’s labeling it as “a triumph of humanitarian engineering and one of the greatest gifts ever bestowed on India by the British.” Sure, that might be true but the lack of context is glaring.

All told, this is still a lively and quirky account that’s a revealing slice of India and its people. Tastes better when consumed with samosa and chai.

For the record, my favorite capture of monsoon in Mumbai still remains this Bollywood song from the ‘70s. Moushumi Chatterjee in a sari and Amitabh Bachchan in a suit (!) and the sheer abandon of giving in to the rain. Be still, my heart.