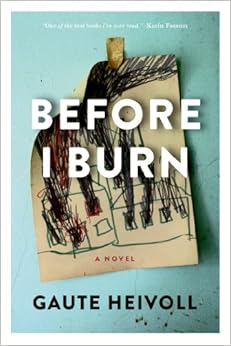

Yes, Before I Burn is about a pyromaniac on the loose in remote, rural Norway in the 70s. But it’s also about much more. The fragile child’s drawing on the cover, curled up and ready to burst into flames, speaks to deeper meanings: about adult expectations set during childhood, and the pervasive melancholy that can accompany stifling parent-child relationships. The dark Lake Livannet, painted hauntingly, is a perfect metaphor for the many anxieties the good people of Finsland bottle. As debut author Gaute Heivoll arrestingly shows, release might not always be forthcoming and if it does, is often ugly.

Saturday, December 21, 2013

Tuesday, December 17, 2013

The Flamethrowers by Rachel Kushner

The Flamethrowers is an exquisitely crafted bildungsroman about Reno, a young woman coming of age in 70’s New York. A formative experience in Italy additionally pupils her about the manifestations of class and the activism that tries to shake its yoke (the book cover is from a magazine released by one of Italy’s leftist organizations, Autonomia Operaia). Through Reno’s attachment to motorcycles, Rachel Kushner effectively works the metaphor of speed -- the exhilarating ride that is youth, the life that passes by in a blur and what we eventually save of it, a few frozen still-frames to learn from and perhaps even love.

Friday, December 13, 2013

Pig's Foot by Carlos Acosta

Pig’s Foot is the translation from the Spanish of Pata de Puerco, a small village in Cuba back to where Oscar Kortico can trace his roots. Trying to make do under desperate conditions in a barrio in Havana, Oscar makes a charming (if brash) narrator as he paints an idyllic picture of the town from the 1800s to more contemporary times. Weaving in splashes of magical realism and snippets of history from the island nation, the author Carlos Acosta, who is also a world-famous dancer, writes an engaging tale that affirms the continued relevance of history in crafting our identities.

A longer review of this title is at Mostlyfiction.com.

Friday, December 6, 2013

Orfeo by Richard Powers

A contemporary retelling of the myth of Orpheus, Orfeo traces the path of an aging nondescript music composer who inadvertently finds himself in a maelstrom of negative media attention. Switching back and forth from the present to the past, Richard Powers outlines the trials of a life spent searching for an ever-elusive objective. Along the way, protagonist Peter Els loses much that he values, yet gains a subtle wisdom. The saying “it takes a lifetime to learn how to live” is truly applicable here. The discrete washes of "color" fluidly merge into one grand composition. Orfeo is a breathtaking performance with nary a discordant note.

A long review of this book was published in the January 22 issue of The BookBrowse Review. Thank you to the publishers for an ARC.

A long review of this book was published in the January 22 issue of The BookBrowse Review. Thank you to the publishers for an ARC.

Tuesday, December 3, 2013

Junkyard Planet by Adam Minter

One look at the heap of scrap on the cover and it would be easy to assume that Junkyard Planet is filled with preachy directives about consumption. But it’s this book’s subtitle that’s closest to what Adam Minter so adroitly achieves. Minter tracks our recyclables (including paper and even Christmas tree lights) as they are shipped to countries like China satisfying its insatiable demand for raw materials. While I would have loved learning more about the hows of the business, Junkyard Planet emerges nevertheless as an insightful look at an industry that is one of the many byproducts of consumerism.

A longer review of this title is at Mostlyfiction.com.

A longer review of this title is at Mostlyfiction.com.

Tuesday, November 26, 2013

The Race Underground: Boston, New York and the Incredible Rivalry That Built America's First Subway by Doug Most

The path from horse-drawn carriages in the late nineteenth century to electric subways was not always a linear solution, nor was it easy. Relief from congestion in Boston and New York, two of the country's early-growth cities, was to be the metaphorical “light at the end of the tunnel.” It is interesting that today, any grander agenda for the expansion of subways -- or public transportation in general -- seems to have taken the back burner, superseded by Americans' love of the automobile.

Nevertheless Doug Most's chronicle of how the subways got their start in two of the most dynamic metropolises in the United States makes for riveting and compelling reading. Highly recommended, especially for history geeks.

Anything That Moves: Renegade Chefs, Fearless Eaters, and the Making of a New American Food Culture

The empty plate on the cover of Anything Moves is fitting for the blank canvas possibilities today’s world of food presents. As New Yorker writer, Dana Goodyear shows us, there are many who are pushing the boundaries of what to present on a plate and how. Atomized lavender anyone?

The book is mostly Goodyear’s reporting pieces from The New Yorker cobbled together and the lack of a cohesiveness to the entire volume, sometimes peeks through. Nevertheless this is an infinitely engaging and delicious look at avante-garde cuisine in the United States and the players and foodies who make it happen.

A longer review of this book is at BookBrowse.com.

A longer review of this book is at BookBrowse.com.

Thursday, August 22, 2013

Review: The Explanation for Everything by Lauren Grodstein

Wasn’t the Garden of Eden just perfect until that nasty

snake came along? Melissa Potter believes so. It’s up to her, she knows, to chase

the “snakes” out – to make believers out of people like Andrew Waite, her college

biology professor, an avowed atheist. In her compelling new novel, Lauren Grodstein

shows that our views on religion are mostly a matter of perspective. What

really is the explanation for everything? Is it God? Or is it science? As

Melissa and Waite explore these profound questions, they find that neat

explanations are hard to come by and the “other side” difficult to

compartmentalize.

Sunday, August 18, 2013

Review: Asunder by Chloe Aridjis

Years ago, it was suffragette Mary Richardson who took a cleaver to Velasquez's Rokeby Venus but that wound continues to haunt Marie, a guard at London's National Gallery. The cracks and tears that paintings take on over time, she realizes, are much like the strains people are subjected to as well. As Marie struggles with the weight of her past and the release that is waiting like a coiled spring to finally materialize, the reader is treated to some poetic imagery and an incisive exploration of the slow burn of life for an everywoman who is just coming into her own.

Sunday, August 11, 2013

Review: The Secret History by Donna Tartt

It is only fitting that Artemis, the goddess of fertility

and hunting, graces the cover of Donna Tartt’s superbly paced debut thriller,

The Secret History. In a nod to the goddess of “swift death,” a closely knit group of college students, studying the

classics at a small Vermont liberal arts institution, kills one of its own. In the echo chamber that results, morality walks on a slippery slope. This

coming-of-age story (with glorious descriptions of Vermont) beautifully explores uncomfortable questions about ethics

and courage. What’s scary here is not the crime itself but just how darned

plausible Tartt makes it all seem.

Friday, April 26, 2013

Review: American Dream Machine by Matthew Specktor

Early on in the powerful book, American Dream Machine, the twenty-something narrator Nate Rosenwald makes his intentions clear. "This story I have to tell doesn't have much to do with me," he says, "but it isn't about some bored actress and her existential crises, a troubled screenwriter who comes to his senses and hightails it back to Illinois. It's not about the vacuous horror of the California dream. It's something that could've happened anywhere else in the world, but instead settled, inexplicably, here."

Read the rest of the review at BookBrowse.com.

Review: Z A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald by Therese Ann Fowler

When it comes to American literature's golden "it" couple, it was hard to tell if life imitated art or if it was the other way around. Scott Fitzgerald once said, "Sometimes, I don't know whether Zelda and I are real or whether we are characters from one of my own novels." The glamorous power couple that captured the public's imagination in the Jazz Age occupies center stage in Therese Ann Fowler's new book, simply called Z. Zelda narrates the heartbreaking love story, and while this is fiction, much of it stays true to the Fitzgeralds' real-life trajectory from a young couple madly in love, to their excesses, and eventual falls.

Read the rest of the review at BookBrowse.com.

Review: A Map of Tulsa by Benjamin Lytal

Jim Praley is not quite sure what to make of Tulsa, the city where he grew up, and went to high school; the city he was a little too eager to leave behind when he finally left for college. At the start of Benjamin Lytal's soulful debut, A Map of Tulsa, Jim has finished his first year of college and is back home in Tulsa for the summer. Already the prodigal son act is one marked with defeat – Jim only returns home because he didn't get a summer job with the campus newspaper. Never mind, he tells himself, he will set a systematic course of study over the summer, one that will leave him amply prepared to choose a major, come sophomore year. "I came back to Tulsa that summer for different reasons. To prove that it was empty. And in hopes that it was not," Jim says.

Read the rest of the review at BookBrowse.com.

Review: How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia by Mohsin Hamid

"There was a moment when anything was possible. And there will be a moment when nothing is possible. But in between we can create." It is this grand arc – one between life and death – that the talented Mohsin Hamid traverses in his compelling new novel, How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia. The unnamed narrator, simply written as the second person "you," knows he has to "create" – a family, a business, a life – a life that moves him far beyond the restrictive confines of his poor village childhood.

Read the rest of the review at BookBrowse.com.

Review: Salt Sugar Fat by Michael Moss

I can see you rolling your eyes already. "Yes," you say, "I know that too much salt, sugar and fat are bad for me." After all, you've probably at least come across Michael Pollan's commandment: "Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants." You don't really need to read another killjoy volume, you think. Well, think again. The absolutely brilliant Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us is a well-researched and well-reported book that despite its loaded subject, doesn't sound preachy and never wags its finger at you, the end-consumer.

Read the rest of the review at BookBrowse.com.

Review: All That Is by James Salter

The cinematic first chapter of James Salter's new book All That Is is set during World War II, during the Battle of Okinawa, when American forces were slowly "prying" many an island from the Japanese. The chapter serves as a perfect frame of reference for the three men who make up most of its narrative: there's dashing Kimmel who always boasts about his sexual exploits, pious Brownell, who's constantly embarrassed by details about Kimmel's escapades; and finally, Philip Bowman, a run-of-the-mill obedient deckhand who is diligent and does as he's told. While this first chapter is very unlike the rest of the novel, it serves to give us a sneak peek at the characters' personalities and discover how they change (or not) during the course of their lives. Soon the war ends, the camera zooms in and the rest of the book focuses mostly on Bowman as he returns home to the rest of his life.

Read the rest of the review at BookBrowse.com.

Review: Where'd Do You Go Bernadette? by Maria Semple

The good people of Seattle might find something "hinky" about Bernadette Fox, the protagonist in Maria Semple's Where'd You Go Bernadette? As the story opens, Bernadette is a stay-at-home mom, always hiding behind dark glasses. She hates to mingle with the parents at her daughter Bee's private school, refers to the pesky school moms as "gnats," can't stomach how parking in Seattle is an elaborate eight-step procedure – and she detests the five-way intersections the city seems to be full of.

Read the rest of my review at Bookbrowse.com.

Review: The Burgess Boys by Elizabeth Strout

Jim Praley is not quite sure what to make of Tulsa, the city where he grew up, and went to high school; the city he was a little too eager to leave behind when he finally left for college. At the start of Benjamin Lytal's soulful debut, A Map of Tulsa, Jim has finished his first year of college and is back home in Tulsa for the summer. Already the prodigal son act is one marked with defeat – Jim only returns home because he didn't get a summer job with the campus newspaper. Never mind, he tells himself, he will set a systematic course of study over the summer, one that will leave him amply prepared to choose a major, come sophomore year. "I came back to Tulsa that summer for different reasons. To prove that it was empty. And in hopes that it was not," Jim says.

Read the rest of my review at BookBrowse.com.

Friday, March 22, 2013

Review: Life After Life by Kate Atkinson

According

to the basic tenets of Hinduism, life is a continuous spectrum into

which you are born as different embodiments. The opposite of death,

therefore, is not life, it’s birth. The path one follows along one such

reincarnation might follow a predetermined pattern, but what shape would

that path take if you threw in random tweaks here and there. What

happens if you don’t die of an umbilical cord strangling you blue, if

instead of getting swept away by the ocean waves, a kind stranger

rescues you when you’re a little girl playing with your sister. These

are the very questions that the immensely talented Kate Atkinson

addresses in her latest book, Life After Life.

Ursula

Todd, the central character in the novel, is born on a cold, snowy

night in 1910. In her first reincarnation she barely lives a few minutes

having been born with the cord wrapped around her neck. In subsequent

births, however, she gets further along until in the last variation she

lives to be a old lady who has lived through and seen the worst of the

World Wars, especially World War II. As a child, she is taken to a

doctor because her trying mother, Sylvie, assumes there is something

just slightly off about her younger daughter. Ursula seems to see things

that have happened before in a pattern of deja vu. She knows she is

different somehow but can’t seem to grasp what it is about her that

makes her so.

Ursula

lives through a time in history where women didn’t really have a large

range of options. A potential career would be a school teacher or a

secretary in some government office. Marriage and motherhood, if they

happened, were expected to provide succour, but they often didn’t. To

accept these social confines, Ursula follows Nietzsche’s basic

principle, “Amor fati.” “ It means acceptance. Whatever happens to you,

embrace it, the good and the bad equally,” she says.

So it is that she embraces life with complicated family dynamics, an abusive marriage and even war. The Greek poet, Pindar is quoted here: Become such as you are, having learned what that is. In the case of Ursula, that learning is a minor miracle to behold. When she finally becomes all that she is, you realize that it’s as much about the journey as the final outcomes. Kate Atkinson’s dazzling new novel shows us how life in all its glory can still turn on a dime. Its beauty lies in the transitory and completely arbitrary nature of everything that passes us by. “Time isn’t circular, it’s like a palimpsest,” writes Atkinson. As Life After Life shows, we choose to inscribe it with the details of our lives, most of them bland and ordinary, but interspersed with some utterly breathtaking moments that take our breath away.

Saturday, February 16, 2013

Review: All The Light There Was by Nancy Kricorian

The setting is World War II Paris -- when the Germans begin their occupation of the city, the protagonist of this story is just turning sixteen. Maral Pegorian and her older brother, Missak, are part of an Armenian family displaced to France after the Armenian genocide. They are stateless refugees and have made the suburb of Belleville in Paris, their home. Maral’s father is a cobbler and owns a small shoe shop hoping to one day pass on his skills to his son.

Missak, on the other hand, has different plans. He is a skilled artist and wants to work as an apprentice at the local print shop while spending most of his time secretly helping the French resistance. As a girl from a fairly conservative family, Maral can’t do much to help her brother, even if she sometimes wishes she could. “Was this to be my lot? Stuck in an apartment knitting or sewing or cooking while waiting for the men to come back from some adventure? It made me want to take the kitchen plates and throw them out the window just to hear them smash into a thousand pieces on the cobblestones below,” she laments.

Easily the smartest in the family, Maral goes through school even with the war progressing all around her, and towards the end of the story, graduates with an offer of admission to one of France’s most prestigious universities.

The Pegorian family’s fate is not unique to Paris or even to Armenians. Their neighbors, the Kacherians (also Armenian) are scraping the barrel to get by as are the many mixed families (including Jewish folks) in the neighborhood. Food is hard to come by -- it’s mostly bulgur and turnips that the Pegorians manage to finagle with their ration card. There’s hardly any butter or meat to be had and even onions can be a rare delicacy. Despite the evident sufferings of the citizens during the Occupation, the children somehow manage to be themselves. Maral, in fact, falls in love with Zaven, one of the Kacherian sons, and Missak’s best friend. The two meet surreptitiously and pledge themselves to each other. Yet the best laid plans don’t always come to fruition.

Zaven and his older brother, Barkev, are swept up by the force of history and spend time in a German camp which changes them forever. The war crimes they witness leave permanent scars on their psyches -- and ripples from these will eventually touch everyone they know including Maral.

History plays out in more than one way in this touching novel by Nancy Kricorian. With the weight of the Armenian genocide on their shoulders, the Armenian families in All The Light There Was, only want to lie low and not be subject to more tragedies. Maral’s parents have witnessed the horrors of the massacre personally and understandably it defines their life perspective in many subtle ways. When a Jewish family next door is rounded up by the Germans, the Pegorians hide the youngest girl in that family in their own apartment until the child is ready to be shipped to her aunt in Nice.

The Armenians in Maral’s generation might be removed from the immediate horrors of the Armenian genocide but they use the lessons learned from it to know that survival depends on many complicated factors. They are not ready to judge when they see their fellow brethren wear the American or the German uniform in the war.

In the end this story is a coming-of-age tale about Maral, a girl of promise at the novel’s start but who gradually gets worn down as the story moves along. “This is the story of how we lived the war, and how I found my husband,” Maral says at the beginning. The path toward finding her husband is not necessarily the most optimal but of course this is wartime and everyone’s lives are shaped by it. For someone who was fairly strong-willed at the beginning, it is a little frustrating, if understandable, to see Maral give up her education and instead fall into what comes more easily.

All The Light There Was is told through Maral’s voice and her perspective. In one sense, since she doesn’t do much except to bear witness to events that happen around her, this point of view feels limiting at times. The lens is never trained away from Maral and it occasionally gets claustrophobic. Yet it is precisely because the story is told through Maral’s voice, that the reader gets to feel what life was like for everyday citizens in occupied Paris. You realize that even during the worst wars, life can plod along -- and even shine through -- with grace. The beautiful cover art in this book drives home the point gracefully. Maral and her boyfriend are up front, lost in each other, while the rest of Paris goes on around them. You realize that while teenagers are often self-centered anyway, in times of war, this can be an essential mechanism to get through its many tribulations.

Ultimately the story ends with a ray of hope. “This world is made of dark and light, my girl, and in the darkest times you have to believe the sun will come again, even if you yourself don’t live to see it,” Maral’s father once tells her. As the reader turns the last page, you hope that the sun will indeed come again and shine down on the young and vibrant Armenians.

Review copy courtesy of NetGalley.

Wednesday, February 13, 2013

Review: Small Kingdoms by Anastasia Hobbet

In the period right after the first Gulf War, an uneasiness hung all over Kuwait—its residents forever waiting for Saddam Hussein to strike again. As an American expat in the country for five years around that same time period, author Anastasia Hobbet witnessed this unease first hand. It forms a perfect backdrop for her novel, Small Kingdoms, which tells the story of an assorted set of Kuwaiti and American characters.

The rest of the review is here.

Review: The Rainbow Troops by Andrea Hirata

The Muhammadiyah school in Belitong island in Indonesia is just about ready to fall apart at the seams-- worse, the government officials looking to close the school down will be only too happy to do so. There are big gaping holes in the roof, animals saunter in and out of the classroom, the medical kit is sorely lacking; there aren’t even the requisite pictures of the nation’s leaders on the wall. Yet the school is blessed with two of the most devoted teachers any child could ask for: Bu Mus (who is herself young enough to be in middle school) and Pak Harfan. These two are determined to educate the 11 elementary school-aged children they have in their charge, and they manage to do so despite seemingly insurmountable odds.

The rest of the review is here.

Friday, February 8, 2013

Review: Tenth of December: Stories by George Saunders

Even if I might not be a big fan of the short story form, there are three authors whose short stories are so incredibly arresting I will never pass on a chance to read them. George Saunders is one of them -- the other two are Jhumpa Lahiri and Junot Diaz. I was first introduced to Saunders’s work when I picked up Pastoralia many years ago -- and have been hooked ever since.

Saunders has been referred to as one of the greatest American writers and especially as one for our times. It is his ability to entirely grasp (and succinctly document) the fading American dream that makes his work so utterly compelling and yes, breathtaking. His latest collection, Tenth of December, hits the bullseye yet again.

In a recent appearance on The Colbert Report, Saunders was asked why he liked to write short stories. “America likes big,” Colbert reminded Saunders, adding that he typically liked to pay for books by the pound. Saunders explained that he likes the short-story format because it compels you to get your point across with an economy of words. Interestingly enough, Saunders likes to compare a short story to a joke. It has the same genetic makeup, he argued on the Report. You have just a short amount of time to leave the audience exhilarated or let down. Saunders’s most recent short story collection achieves the latter. His stories are absorbing and incredibly touching.

There’s the downright scary “Victory Lap” which describes the attempted kidnapping of a young girl, through the eyes of a teenaged boy across the street. What’s especially compelling about this story is that it paints the picture of not just one, but three tortured souls -- the girl, the boy, and the criminal. The slow extent of the crime creeps up insidiously and the reader can’t help but watch as the crime unfolds.

There’s also the fantastic science fiction look at contemporary love in “Escape from Spiderhead” when an ex-convict young man is given increasingly higher doses of various medications to make him love someone he might not be attracted to. “What a fantastic game-changer. Say someone can’t love? Now he or she can. We can make him. Say someone loves too much? Or loves someone deemed unsuitable by his or her caregiver? We can tone that shit right down.”

The best of Saunders’s work is a brilliant reflection about class in America. He achieves this not just through the stories he narrates but through the language he uses as well. In the absolutely wonderful, “Home,” a character named Harris says, “A boat could be for boys or girls. Don’t be prejudice.” This same story, one of my favorites in the collection, describes a washed-up court-martialed war vet trying to get back into his life. “Thank you for your service,” he is told wherever he goes, in what could be interpreted as a case in irony. Meanwhile, Harris’s mother and her new boyfriend are hanging on by the most tenuous of threads while his ex-wife and her new husband have a fancy house across the river. “Three cars for two grown-ups. I thought. What a country. What a couple selfish dicks my wife and her new husband were. I could see that, over the years, my babies would slowly transform into selfish-dick babies, then selfish-dick toddlers, kids, teenagers, and adults, with me all that time skulking around like some unclean suspect uncle.”

“That part of town was full of castles,” Harris points out, “Across the river the castles got smaller. By our part of town, the houses were like peasant huts.” As Saunders so brilliantly points out, at its most basic essence, life can indeed be boiled down to a fairy tale. The rich get to live in castles while the poor languish in peasant huts. And in this fairy tale, poverty plays a very effective villain--one that is very, very hard to slay.

Galley copy courtesy of Netgalley.

Sunday, January 20, 2013

Review: The Forgiven by Lawrence Osborne

At its core The Forgiven sets out to be a story about the clash of values - between east and west. But the Westerners at least, seem so tone-deaf to the cultural mores of Morocco that clashes, if any, seem contrived...What Osborne really succeeds in doing is writing a terrific travelogue - which is unsurprising considering that he is an experienced travel writer. The Moroccan desert comes superbly alive in the novel - every detail is meticulously outlined...The novel is worth reading for this reason alone.

The rest of the review is at BookBrowse.

Thursday, January 17, 2013

Review: The Garden of Evening Mists by Tan Twan Eng

Early on in the evocative new novel, The Garden of Evening Mists, the protagonist Teoh Yun Ling comes across an arresting pair of statues in her friend's tea estate gardens. It is only fitting that one of them is Mnemosyne, the Greek goddess of memory. The other one, Teoh Yun Ling is told, is her twin, the goddess of forgetting. This vignette might well capture the premise of this fantastic novel by Malaysian author Tan Twan Eng - that we spend almost our entire lives trying to find harmony between the twin pillars of memory and forgetfulness.

The rest of my review is at BookBrowse.

Review: Consider the Fork: A History of How We Cook and Eat by Bee Wilson

I can never remember my grandmother without remembering the smoke-filled kitchen she worked in day in and day out. One of her best creations was rasam, the lentil broth soup that is the cornerstone of South Indian cooking. It wasn't until I tried my hand at recreating the dish in the heat of her kitchen that I realized what a precise science the dish was, even though grandma seemed to churn it out daily with such nonchalance. The secret ingredient she swore by? A special pot called an eeya chombu, made with an alloy containing tin and other metals. My ninth grade self didn't realize that eeya chombu translated to "melting pot" - quite literally. Venturing into the kitchen one day while grandma was having a shower, I decided I would surprise her with a rasam of my own. I could do it. I had seen her make it many times, after all. But to my horror, as the soup gradually began to simmer and then violently boil over the untamed fire, the pot simply melted away. Not only had I lost my rasam but also my grandma's precious pot! Grandma, bless her soul, took in the scene of the crime with an extra dose of equanimity and Dad replaced the pot that very evening. All's well that ends well and my accident was forgiven and forgotten.

It was that temperamental kitchen tool - my grandma's eeya chombu pot - that I was reminded of while reading Bee Wilson's fascinating historical account of the implements we use in working with one of humankind's most basic drivers - food.

The rest of my review is at BookBrowse.

Review: Detroit City is the Place to Be by Mark Binelli

When Mark Binelli, a native of Detroit, and general assignment reporter, began work on a book about the city, one of his interview subjects asked him if the book was going to be fiction or non-fiction. "Non," Binelli replied. Binelli writes about the guy's reaction: "He snorted and said, 'No one's gonna believe it.'"

A large portion of Binelli's engaging book, Detroit City is the Place to Be, covers the stuff that "no one's gonna believe." No one, for example, is likely to believe that a once thriving boomtown had gone into such utter and total ruin. Large swathes of empty land, horrendous crime rates, and unemployment – if these issues are bad in urban areas around the country, they are much, much worse in Detroit. "If, once, Detroit had stood for the purest fulfillment of U.S. industry, it now represented America's most epic urban failure, the apotheosis of the new inner-city mayhem sweeping the nation like LSD and unflattering muttonchop sideburns," Binelli writes.

The rest of the review is at BookBrowse.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)