Wednesday, December 21, 2011

Review: The Great Fire by Shirley Hazzard

Excerpt

Coming more than twenty years after her critically acclaimed Transit of Venus, Shirley Hazzard's latest, The Great Fire, is in most basic essence, a classic old-fashioned romance. The novel traces of the path of the protagonist, Maj. Aldred Leith and his love, seventeen year-old Helen, as they try to live out lives anew in the aftermath of the Second World War.

The rest of the review, originally published on November 3, 2003, can be found here.

Review: The Movies of My Life by Alberto Fuguet

Excerpt

The incredibly creative plot device that steers Alberto Fuguet's novel The Movies of My Life centers around a list-a list of 50 movies that forms a brilliant vehicle to explore a lonely childhood.

The rest of the review, originally published on November 28, 2003, can be found here.

Monday, December 19, 2011

Review: Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? By Mindy Kaling

Mindy Kaling’s publisher’s research analytics are correct: I am indeed one of the “Aunts of America” who was totally intent on buying her book for my niece—and my daughters. But now that I have read Kaling’s absolutely delightful volume, I am loath to part with it. I’ll just have to get each one of the girls a copy of this wonderful book.

The children of South Asian immigrant professionals, Kaling writes about her childhood years with honesty and wit. Kaling’s descriptions of her high school clique and her subsequent falling out of it, are especially hilarious. Kaling consoles readers that being quiet and patient in high school has its own rewards—there’s no point in peaking early, she points out.

She can’t understand high-schoolers who use the Mellencamp song, “Jack and Diane,” as their anthem. “I guess I find “Jack and Diane” a little disgusting,” Kaling writes, “As a child of immigrant professionals, I can’t help but notice the wasteful frivolity of it all. Why are these kids not home doing their homework? Why aren’t they setting the table for dinner or helping out around the house?”

“The chorus of “Jack and Diane” is: Oh yeah, life goes on, long after the thrill of living is gone. Are you kidding me? The thrill of living was high school? Come on, Mr. Cougar Mellencamp. Get a life.” Touché.

After high school, professional success takes its time reaching the Dartmouth grad. Her struggles to get the career she wants are outlined beautifully and all through, Kaling never loses her sense of humor and her ability to make the best out of even the most discouraging situation. At a babysitting gig in New York City, she is thrilled to be consuming the kids’ food. “Kid-friendly food is the best, because kid-friendly simply means ‘total garbage.’ I ate frozen chicken nuggets shaped like animals, fruit chews shaped like fruit, and fruit shaped like cubes in syrup,” Kaling writes. “I discovered that kids hate for any food to resemble the form that it originally was in nature. They are on to something because that processed garbage was insanely delicious.”

Eventually Kaling gets the break she wants: She is part of a two-person show off Broadway (that she co-writes) and that show’s success opens doors for her in Hollywood. Kaling writes about these accounts well and about the role, which she is best known for—as staff writer for the television sitcom, The Office.

Kaling’s work ethic, largely influenced by her parents, shines through in the work she produces of course, (even if she says she gets distracted often) but she also makes an explicit point of it in her memoir: “In my entire life, I never once heard either of my parents say they were stressed. That was just not a phrase I grew up being allowed to say. That, and the concept of ‘Me time.’”

Her personality comes through loud and clear in many cases but you particularly root for her when during a photography session, she is presented only a few dresses all in size 0. There is only one boring navy shift in her size 8. Kaling insists on having a styling professional change a size 0 dress to make it work for her.

There are two things, which I hoped Kaling had addressed in the book and she does not: how she landed her agent Marc Provissiero and her thoughts on the limited number of women writers in comedy. “I just felt that by commenting on that in any real way, it would be tacit approval of it as a legitimate debate, which it isn’t,” Kaling writes. Her stance is understandable, but still it’s hard not to look at it as a soapbox opportunity, lost.

When I mentioned that I was looking forward to reading Kaling’s memoir to a friend, she said she was hesitant to read it because she was not too crazy about Kelly Kapoor on The Office. This, as the memoir outlines, is one of Kaling’s worries. “Obviously this confusion is not something I would mind if I were playing Lara Croft or a Supreme Court justice or Serena Williams or something, but when you’re playing a bit of a selfish, boy-crazy narcissist, it’s a concern,” she writes. Kaling goes on to list just how many ways she is different from her on-screen character.

By the end of the book, you come to realize that Kaling is most definitely not Kapoor. Kaling is a class act and a worthy role model for my niece and each of my two daughters. There is no further proof of this than this one sentence in which Kaling outlines the things that break her heart: “Valet Guys Who are my Dad’s Age: I can’t even deal with this. When I see a man who is around my father’s age running down the street to get a car, it breaks my heart,” Kaling writes. That one sentence captures Kaling’s essence: warm, loving, and above all, someone with a deep sense of empathy. It also helps that she is very, very funny.

Review: Chango's Beads and Two-Tone Shoes by William Kennedy

Excerpt

History has shown us that the instruments of revolution can be as varied as the causes they support; the Changó’s beads and two-tone shoes in William Kennedy’s new novel are precisely that—they’re stand-ins for the vehicles of change.

The rest of the review is here.

Review: Quite Enough of Calvin Trillin: Forty Years of Funny Stuff by Calvin Trillin

"There was a discussion at my house recently about whether or not I am an uncultured oaf. This is not the first time the subject has come up."

We have the “parsimonious” Victor S. Navasky to thank. Many years ago, he commissioned the wonderful writer Calvin Trillin to write regularly for the Nation, the magazine, which Navasky then edited. The project was “a thousand words every three weeks or so for saying whatever’s on my mind, particularly if that’s what on my mind is marginally ignoble,” Calvin Trillin recalls in one of many essays in his new collection, Quite Enough of Calvin Trillin. That regular project combined with Trillin’s famous deadline poetry made him one of America’s foremost humorists.

The rest of my review can be found here.

Thursday, December 15, 2011

Ten Myths about Telecommuting, Busted!

I am fortunate enough to telecommute to my job for the past five years. Since I often get asked questions about the arrangement, these answers should help.

Ten Myths About Telecommuters, Busted!

1. Telecommuters throw in a load of laundry or empty the dishwasher in lieu of water cooler breaks.

False. It’s bad enough keeping the stuff to do at work straight instead of having to mix it with Tide or Ajax.

2. Telecommuters get to work in their PJs.

There is a chance the webcam could suddenly demonstrate owl-like motor tendencies and, you know, air your wares to an unintended audience. Most of us play it safe by wearing work clothes to “work.”

3. Telecommuters are antisocial hermits because they are cut off from all human interaction.

If you label water cooler small talk “human interaction,” guilty as charged. But most of us have friends we hang out with regularly—time spent precisely because we were not caught in long, white-knuckled commutes during the day.

4. Telecommuters work all the time—24/7.

False again. Maintaining a strict work schedule is essential to one’s sanity. Besides, no time for laundry means no time for work clothes. In which case, revisit point #2 above.

5. Telecommuters just don’t work at all.

As tempting at that proposition might be, no work output = no job.

6. Telecommuters are not very productive.

Since most of us recognize that telecommuting is still a privilege, we try not to abuse it. Time spent watching cats playing piano on YouTube is kept to a minimum. It’s surprising how much time is also saved by not having to linger at a water cooler or take frequent bathroom breaks.

7. A telecommuter is available to take my dog out for his daily constitutional.

Even if telecommuters work from home, the key word here is “work.” We’re happy to come to the rescue and help when needed. But as much as we love Spot, it’s hard to break away and oblige every single day. Or maybe there is some truth to #3.

8. Telecommuters have wild flings with the mailman.

False again. Work gets in the way. Besides, mailmen are scared of dogs. Also see #5 above.

9. There is absolutely nothing about a daily commute that telecommuters miss.

This is very, very, very nearly true. We definitely do not miss the endless drives in snow and rain. The hour-long commutes. The mind-numbing fund drives on NPR. But we do miss the transition that a drive allows from work matters to home matters. Telecommuters are often called upon to switch gears from work to bake sales in a span of 30 seconds—no easy task.

10. Without Starbucks or Dunkin’ Donuts, telecommuters have to make do with bad, watery coffee.

Wrong. Money saved on gas in the first year alone is more than enough to invest in a good personal cappuccino machine.

Review: Bangkok 8 by John Burdett

Excerpt

Krung Thep means City of Angels, but we are happy to call it Bangkok if it helps to separate a farang from his money." So says Detective Sonchai Jitpleecheep in John Burdett's racy thriller, Bangkok 8.

The rest of the review, originally published on July 8, 2003, can be found here.

REVIEW: Shadow Without a Name by Igancio Padilla

Excerpt

"My father used to say his name was Viktor Kretzschmar. He was a pointsman on the Munich-Salzburg line and not the type to decide, on the spur of the moment, to commit a crime."

So begins the brilliant Shadow Without a Name, a book that doubtless deserves the award for best opening lines in a novel in recent memory. The narrator here is Franz Kretzschmar, a young recruit in the Third Reich, haunted by questions of identity--both of his own and his father's. As he recounts, on an old dilapidated train long ago, Viktor Kretzschmar met Thadeus Dreyer. Both expert chess players, a deal was struck: "if my father won, the other man would take his place on the eastern front and hand over his job as pointsman in hut nine on the Munich-Salzburg line. If, on the other hand, my father lost, he would shoot himself before the train reached its destination." As a result of that wager, a Viktor Kretzschmar spends the rest of his days as a frustrated pointsman and Lieutenant Colonel Thadeus Dreyer is decorated with the Iron Cross for his actions on the front.

The rest of the review, originally published on June 18, 2003, is here.

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

The New India

|

| This picture of Au Bon Pain in Cambridge, MA, is from www.dogboston.com. |

I had the chance to meet with the wonderful Siddhartha Deb recently. Over chai at Au Bon Pain in Cambridge, Deb talked about his latest book, The Beautiful and the Damned: A Portrait of the New India.

It's a wonderful look at contemporary India, warts and all. Check out my feature for Khabar.

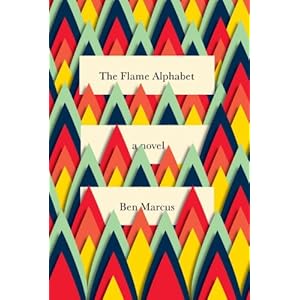

Flames Licking the Title

Ben Marcus's upcoming mind-blowing read, The Flame Alphabet, has one of the most arresting book jackets I have seen in a while. From the ARC, I can't tell if the hardcover will have more of a 3-D element to it but even so, it's fab! I love the idea of the flame collage elements slowly licking away at the title. Awesome design by Soonyoung Kwon for Knopf.

I expect my review to be at CurledUp close to the release date of January 17. Pre-order the book now!

REVIEW: White Mughals by William Dalrymple

Excerpt

William Dalrymple shot into fame as a travel writer with his In Xanadu, a travel account he wrote when just twenty. A self-confessed Indophile, many of his subsequent works (City of Djinns, Age of Kali) were set in India. His latest book, White Mughals, revisits India, and among other things, is a detailed history of Deccan politics during the late eighteenth century.

The rest of the review, originally published on June 18, 2003, is here.

REVIEW: The Book of Salt by Monique Truong

Excerpt: The Book of Salt is a brilliant debut by a young Vietnamese American, Monique Truong. The novel will certainly place her as one of the brightest young stars on the American literary scene. In her novel, Truong uses the famous literary couple Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, as a background against which to tell her tale. Many details about the couple are known including the fact that they had in their employ, a young Vietnamese chef. Not much, however, is known about the chef. Truong creates instead a superb fiction narrative about him and the reasons for his forced displacement.

The rest of the review, originally published on March 31, 2003, can be found here.

Thursday, December 8, 2011

Our Childhood Baggage

| |

| The culvert I remember was probably a little wider than this one. Taken from nationews.com |

All I remember today is standing frozen at one end of a long and wide culvert, a thin broken wooden plank connecting one end to the other. I remember my father holding my hand and willing me to just jump and cross over to the other side. I couldn't. He tried telling me it was easy but it was not. The gap from one end to the other yawned and stretched before me like an endless chasm. He might as well have been asking me to leap over the Grand Canyon. After a couple of tries, he gave up, held my hand and we walked the longer way over to the other side.

My father probably did not give the incident much thought but what he never saw was the sheer terror only I was privy to. My body had reacted viscerally, it was a totally out-of-body experience and one I would bring up time and time again when faced with similar challenges--going down steep slopes, walking on slippery surfaces, even touching extremely tactile objects.

It was only years later, when my younger daughter was born with a similar problem, that I discovered that this was a real condition with a real name--sensory integration dysfunction. This was a disorder that was treatable when caught in early childhood. My daughter's was caught and treated. For me it was too late. I still live in mortal fear of even the slightest inclines and icy walks. The saving grace though is that I know my fears are not imagined but real. Equally important, they were validated by people other than my own self.

Today's wonderful essay in the New York Times by Lavanya Sunkara brought these memories rushing back. Like me, she too lived her childhood in shame, not knowing why her body was acting the way it did. Like me, it was only in the United States, that she discovered it was okay to be who she was--to come out of her shell and make the person within shine.

There are many, many things I love about my adopted country and one of them is this: every person is respected. Every child is brought up to live up to his or her full potential.

By not diagnosing my issues early on (like Lavanya, I too had to visit the bathroom nightly with company and that was yet another 'condition') my parents were not guilty of anything. What society as a whole was guilty of however, was shrouding issues like these in secrecy and shame, for not fully giving a child a voice."It's all in your head," was an established way of undercutting a child's very real fears--and this to me, still remains unforgivable.

As Lavanya's example and mine prove, America lets children be heard. Every day, the undersides of beds are checked for monsters. Everybody, even the disenfranchised, for the most part, has a voice. So, like Lavanya, I too will say, "Thank You!"

Review: Monkey Hunting by Cristina Garcia

|

| Large portions of the book are set in Havana's Chinatown pictured above. This picture is from planetware.com |

Excerpt:

Chen Pan is a young 20 year-old in China who signs a contract to make his fortune in Cuba. He is promised that the tropical island is full of riches, that "even the river fish jumped, unbidden, into frying pans." Chen Pan figures he would work in Cuba for a few years, and return to China a rich, content, man. So it is that he signs his life into slavery on a sugarcane plantation in Cuba. The ship journey over to the island is an indication of what lies ahead. After long, hard labor, Chen Pan finally escapes the plantation and makes his life in Havana. Pan's escape from slavery in Cuba and his survival in the country's harsh jungle eventually becomes the stuff of legend.

The rest of this review is here.

Friday, December 2, 2011

Parent Trap?

It's interesting that The Millions' Year in Reading launched yesterday. I saw it roll shortly after I watched this incredible video arguing marriage equality put forth by Moveon.org.

This young man, raised by two lesbian parents, makes a cogent argument for marriage equality. It made me worry that we have not arrived as a country if we need to prove that gay couples can raise stellar citizens. Can they be allowed to be parents only if the kids are perfect? How come heterosexual couples are not held to the same exacting standards?

Which is a perfect segue for my favorite book of 2011--The Family Fang by Kevin Wilson. The book is a perfect example of why not everybody should become parents. The self-absorbed parent Fangs, completely caught up in their art, wreak total havoc on the kids. It's worth a read. At the very least the arguments it puts forth in such a breezy fashion, will resonate long after the last page has been turned.

This young man, raised by two lesbian parents, makes a cogent argument for marriage equality. It made me worry that we have not arrived as a country if we need to prove that gay couples can raise stellar citizens. Can they be allowed to be parents only if the kids are perfect? How come heterosexual couples are not held to the same exacting standards?

Which is a perfect segue for my favorite book of 2011--The Family Fang by Kevin Wilson. The book is a perfect example of why not everybody should become parents. The self-absorbed parent Fangs, completely caught up in their art, wreak total havoc on the kids. It's worth a read. At the very least the arguments it puts forth in such a breezy fashion, will resonate long after the last page has been turned.

Thursday, December 1, 2011

Banana Beer

After reading Naomi Benaron's wonderful book, Running the Rift, to be released in January, I now want to try banana beer.

The Manifestation of Cowardice: You Deserve Nothing

|

| The protagonist is an English teacher at the International School of Paris. |

Silver is the object of worship by all his students. He is a very likeable and loved teacher at the ISF, the International School in Paris, for American expats. Despite his teaching abilities Silver has deep moral failings. His students, who true to form, expect him to be a hero both inside and out of the classroom, are deeply disappointed when he wimps out. Silver might coerce his students to take to the soap box and fight for what they believe in, but he himself doesn’t practice what he preaches. This fall from grace is beautifully realized by Maksik through one of the voices that narrates the story—that of Gilad, a boy in Silver’s class.

Till the end Will remains a tad obtuse but Maksik does reveal that he has deserted his wife back in the U.S. after the sudden trauma of his parents’ death. Here too then is an act of cowardice—made worse by his seeking refuge in the blind affair with an underage girl. This girl, Marie, also slowly realizes she is making love to a ghost—the kids soon understand that adults are not all that they are cracked up to be. They are not heroes, just mostly hypocrites.

What makes You Deserve Nothing so arresting and readable is that it drives home some sobering truths. There are no shining heroes; life is complex; there are shades of moral fallacies in most of us. Will’s moral failings, his cowardice, make him so believably real, so very adult.

You Deserve Nothing takes an age-old story and makes it new. In doing so, it superbly shows us that life does not cough up easy answers. As Will’s colleague rightly points out, “The world disappoints you.” The best one can do then is to muddle along on one’s own internal moral compass—hoping for rare moments of courage and integrity in our darkest hours. It will have to do.

The picture of the school is from the ISP website.

Just My Type

Have you ever noticed how menus in fancy restaurants are always set in Papyrus? my daughter asked me a year ago. Until then I had not paid much attention to typefaces. But suddenly I saw them everywhere. The most egregious font violations--such as Sans Serif on hospital donation bins--were especially hard to take.

Simon Garfield's new book Just My Type, is a fun look at the history of fonts. I reviewed the breezy book for Bookbrowse.

Simon Garfield's new book Just My Type, is a fun look at the history of fonts. I reviewed the breezy book for Bookbrowse.

REVIEW: The Coffee Trader by David Liss

|

| The Coffee Trader is set in the city of Amsterdam. |

Excerpt

It is 1659 in Amsterdam, a city which has defeated the Spanish and which has established itself as a strong hub of commerce. The thriving city is home to many Jews who have escaped the Inquisition and want to live here quietly under the strict supervision of the Ma'amad, the governing council of the Portuguese Jews. Miguel Lienzo is one such Jew who makes his living trading in futures and stocks on the floors of the Exchange. Lately, Lienzo has run into trouble. He has lost a lot of money in the sugar market and his brandy futures are looking questionable. He is in debt and is being hounded by Joachim Waagenaar, who "wants his money back." In addition, Miguel has a sworn enemy in Parido, a prominent member of the Ma'amad. Years ago, Miguel backed out of an engagement with Parido's daughter after being caught in bed with her servant. Parido is not one to ignore such slights easily and he is out for blood.

The rest of the review is here.

The picture of Amsterdam is borrowed from this blog.

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Review: Pigeon English by Stephen Kelman

Who’d chook a boy just to get his Chicken Joe’s?

Pigeon English by Stephen Kelman

Around ten years ago, a young Nigerian immigrant, 10-year-old Damilola Taylor, was beaten by boys barely older than him in Peckham, a district in South London. Damilola later bled to death. The incident sparked outrage in the United Kingdom and was subsequently pointed to as proof that the country’s youth had gone terribly astray.

The same incident seems to have also inspired a debut novel, Pigeon English, with 11-year-old Harri Opoku filling in for the voice of Damilola Taylor. As the book opens, Harri has recently emigrated from Ghana to London with his older sister and his mother. Dad and younger sister and the rest of the family are still in the native country and Harri is often brought back to his home country through extended phone calls exchanged between the two sides.

Like most children, Harri is not privy to the intricate goings-on in the lives around him. It’s a fact made worse by the displacement brought about by immigration. Harri must not just figure out the ways of the world, he must do so in a new place where the rules of the game are entirely unfamiliar. Even if life in the ghetto is painful and lived in extreme poverty, Harri finds plenty to keep him in good spirits. For one thing, he wants to try every kind of Haribo (candy) in the store close to him.

Even better he has struck a tentative friendship with a local boy, Dean. With Dean’s help, Harri is determined to solve a recent crime—one where a kid like himself is found brutally murdered in a struggle over a fast food meal. The devastating tragedy affects Harri deeply and he is determined (in a typical naïve and childish way) to find the killers. Unfortunately he gets too close to the real killers—people who might not appreciate interference from a bright-eyed curious kid.

Pigeon English is narrated through Harri’s voice so the English is broken and mixed in with special words whose meanings become apparent only after a few readings. “Bo-styles” for example, means very good while “Asweh” is the more readily understandable, “I swear.”

Harri’s musings and experiences can be funny at one moment and heartbreaking the next. Author Stephen Kelman has done a terrific job in capturing the boy’s voice. The problem with Pigeon English is that the same voice eventually becomes a distraction. It never becomes seamless enough so the reader can concentrate on what the boy is saying—you’re forever hung up on how he’s saying it. And of course there are times when he says too much: “I can make a fart like a woodpecker. Asweh, it’s true. The first time it happened was an accident. I was just walking along and I did one fart, but then it turned into lots of little farts all chasing it.” Did we really need to know that?

It was entirely a coincidence that I read this novel right around the time that the London riots made headline news around the world. As was reported by the New York Times and other news outlets, it was the youth who were the primary looters and criminals in these riots—an effect brought about by a “combination of economic despair, racial tension and thuggery.” The riots, the paper reported, “reflect the alienation and resentment of many young people in Britain.” Read at this particular moment in history, Pigeon English then seems much more than a fairly good read—it also comes across as an important one. One can’t help but wonder how much the timely relevance of its subject matter lead Pigeon English to be shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize this year.

“I made the choice, nobody forced me,” says Harri’s mother about the decision to move her kids to London from Ghana. “I did it for me, for these children. As long as I pay my debt they’re safe and sound. They grow up to reach further than I could ever carry them.” Pigeon English is a moving novel not just because it is a stark story about London’s ghettos, but because it reminds us that for many in the developing world, a move to this kind of a hell is actually a move up.

This review was originally published in mostlyfiction.com.

Review: We The Animals by Justin Torres

“We’re never gonna escape this,” Paps said. “Never.”

We The Animals by Justin Torres

Reviewed by Poornima Apte

We The Animals in this wonderful debut novel refers to three brothers, close in age, growing up in upstate New York. They are the Three Musketeers bound strongly together not just because of geographical isolation but because of cultural separateness too. The brothers are born to a white mother and a Puerto Rican father—they are half-breeds confused about their identity and constrained by desperate and mind-numbing poverty.

This wild and ferocious debut is narrated by the youngest of the three, now grown, looking back on his childhood. It’s a coming-of-age story told in lyrical sentences that are exquisitely crafted. And while there are many moments of beauty in here, there are also ones of searing violence.

The boys can do nothing but stand back and watch as the intensely abusive relationship between the parents plays out everyday and it’s almost worse because the evidence creeps up after the fact. One day, Mom’s eyes are swollen shut and cheeks turned purple “He told us the dentist had been punching on her after she went under; he said that’s how they loosen up the teeth before they rip them out,” the narrator, barely aged seven, recalls. The severe abuse is compounded and made even more heartbreaking by the boys’ innocence and gullibility—they buy this lie and many others, whole.

The daily struggle for survival is heart wrenching yet without melodrama. “We stayed at the table for another forty-five minutes, running our fingers around our empty bowls, pressing our thumb tips into the cracker plate and licking the crumbs off,” Torres writes about one of the many evenings when one can of soup and a few crackers would have to make do for all of them. The boys don’t quite understand why their parents are seemingly happy one moment and why their mother slips into deep bouts of depression the next.

One of the many beautiful chapters in the book is one called “Night Watch” (each short chapter in this slim volume has a name). In it, the boys accompany Dad to work when he finds work at a night job. They have to sleep on the floor in sleeping bags in front of the vending machines, out of plain sight. They are here (and not home) because Mom is at her job working the night shift at a local brewery. The next morning, when a white man comes to relieve Dad of his duties, he spots the three musketeers and can guess at the situation. From the argument that follows, the boys already know that Dad has probably lost this job too. The family’s otherness, especially as perceived by the boys, is just beautifully rendered here.

As the boys enter adolescence, the narrator immediately knows he is separate and apart from his brothers. “They smelled my difference—my sharp, sad, pansy scent,” Torres writes. It wouldn’t be a reveal to say that the difference lies in the narrator’s sexuality, which can be glimpsed early on, if one pays close attention.

In a recent interview, the author Justin Torres has said: “I think that everybody struggles with family in some way and I hope that they can come away realizing that you can go back to those experiences and find something beautiful in everything and that you can make art out of your experiences.” With We The Animals, Torres has crafted just that—a beautiful and memorable work of art. This slender novel packs a powerful punch.

Justin Torres proves you don’t have to pen a giant volume to write precociously about huge themes such as family, race, adolescence and sexuality. Of course Torres writes so beautifully that you almost wish that he did.

This review was originally published on mostlyfiction.com.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)